Yesterday we started working through which Bible to use. We broke off while looking at how the different versions are different and how we can tell. We will pick this up from where we stopped yesterday:

Versions, Cont.

In some cases, for instance, the Douay-Rheims or the NASB, started with another version, the Latin Vulgate and the 1901 ASV respectively, and was then compared to the Greek and Hebrew to revise the earlier version. Again, the introduction will tell you what process the committee followed.

Secondly, the committee works under a translation philosophy. There are two: literal and non-literal. The labels are not quite self-explanatory. If you have any experience with multiple languages you know that a literal translation from one language to another is, if not impossible, it is definitely – well it would be difficult to read and understand.

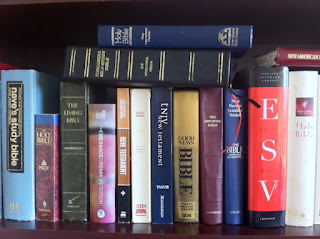

A literal version tries to stay as close to the original languages as possible. The introduction and preface will inform you how the committee will deal with the needs to make the translation readable. Some well known literal versions are KJV, RSV, NASB, ESV.

Non-literal versions choose a different path. They attempt to capture the idea behind the original text. One illustration of this is the NIV. This approach is referred to as dynamic equivalence. Dynamic equivalence is a sense for sense translation (translating the meanings of phrases or whole sentences) with readability in mind (Wikipedia definition, 2020). The advantage of this philosophy is its easier to read. The disadvantage is that it can obscure the structure of the original more than the literal philosophy.

Tomorrow we will look at translations, paraphrases, and at least start on which is better.

Versions, Cont.

In some cases, for instance, the Douay-Rheims or the NASB, started with another version, the Latin Vulgate and the 1901 ASV respectively, and was then compared to the Greek and Hebrew to revise the earlier version. Again, the introduction will tell you what process the committee followed.

Secondly, the committee works under a translation philosophy. There are two: literal and non-literal. The labels are not quite self-explanatory. If you have any experience with multiple languages you know that a literal translation from one language to another is, if not impossible, it is definitely – well it would be difficult to read and understand.

A literal version tries to stay as close to the original languages as possible. The introduction and preface will inform you how the committee will deal with the needs to make the translation readable. Some well known literal versions are KJV, RSV, NASB, ESV.

Non-literal versions choose a different path. They attempt to capture the idea behind the original text. One illustration of this is the NIV. This approach is referred to as dynamic equivalence. Dynamic equivalence is a sense for sense translation (translating the meanings of phrases or whole sentences) with readability in mind (Wikipedia definition, 2020). The advantage of this philosophy is its easier to read. The disadvantage is that it can obscure the structure of the original more than the literal philosophy.

Tomorrow we will look at translations, paraphrases, and at least start on which is better.

It is a daunting search to find an appropriate version that both hold to the truth of the text and is understandably readable. Having grown up spiritually under the "KJV only" era it can also be tragically contentious and distracting from the major privilege of having the Word of the Living God in a form I can understand, if only imperfectly.

ReplyDeleteFortunately the Lord has also given us His Holy Spirit to enable us to understand the truth no matter what the translation. And the search with good friends as well as personal times with the living Spirit each day is a thrilling process.

Thank you for helping us "untrained" ordinary folks to strengthen our pursuit of the stunning truths laid out for us from the time of Creation!

Just returning the favor.

Delete